A new season, and a new batch of 10 Things:

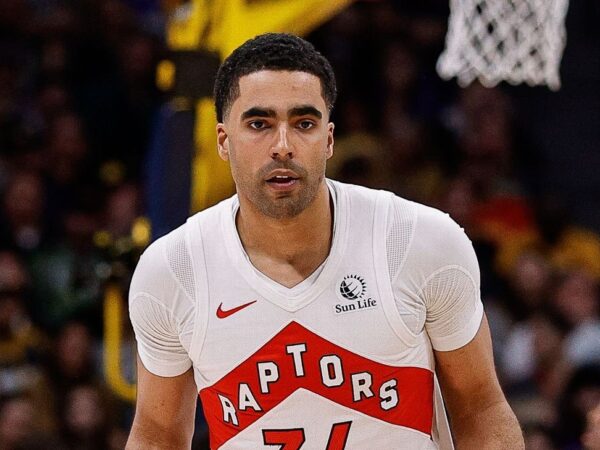

1. The Raptors, everywhere you look

Toronto looks like the most complete team outside whatever basketball hedonism Stephen Curry oversees in the Bay. The Raptors have the versatility to mimic small ball without actually being small, which is the best way to win in the NBA in 2018. Their most frequent starting five — Kyle Lowry, Danny Green, Kawhi Leonard, Pascal Siakam, Serge Ibaka — features two nominal big men, including one in Siakam who can facilitate the offense and legitimately defend all five positions. He might also be the fastest player among those five.

That group is plus-37 in 52 minutes so far. Yikes. The Siakam-Ibaka combo killed in limited time last season; Nick Nurse is smart to give it more run. The Lowry/Green/Leonard trio supplies mega-shooting around it, and Ibaka will make enough 3s to keep defenses honest. Rebounding has been a weakness, as previous coaches feared it might be with Ibaka at center. It hasn’t mattered yet. Meanwhile, Ibaka’s rim protection matters again.

Not much changes when Toronto goes “smaller” and swaps OG Anunoby in for Siakam. Anunoby and Leonard are giant wings — tailor-made to slide up a position. Green has long been one of the league’s premier shot-blocking guards; he morphs into some combination of Carl Lewis and Dikembe Mutombo in transition defense. Lowry is a brainy pest.

The physical tools of both groups are immense. There are various extremities everywhere an offensive player looks — arms in passing lanes, fast feet blockading the paint. A Canadian team named amid mania over an American dinosaur movie has become a hydra.

Toronto’s mental engagement on defense has been just as impressive. The Raptors are dialed in — talking, anticipating, switching in a blink without the teensiest hiccup of confusion or miscommunication. Watch how early Leonard, at first guarding Nicolas Batum under the rim, realizes Green has fallen behind Kemba Walker sprinting baseline — and that a switch is in order:

Leonard slides toward the wing before Walker even arrives at Batum’s screen. Leonard’s switch is only step one. Green reads Leonard’s intentions, and stops at Batum. Take one extra step, and he’d overrun Batum, freeing him for a layup.

Ibaka does nothing, which seems unremarkable. But that nothingness — that sticking to Cody Zeller — is something. A big man thinking even a quarter-step behind might lunge away from Zeller, and toward either Walker or Batum. In panicking over a crisis that doesn’t exist, he would create one. Ibaka sees everything as it happens, and stands pat.

When the Warriors were starting to find themselves in the fall of 2014, their emerging greatness on defense revealed itself in sequences like these — series of three and four rapid-fire decisions, each one an opportunity for a fatal mistake. They negotiated those obstacle courses as if they were nothing. They made high-level switchery look elementary.

Toronto is doing that already, with the greatest individual perimeter defender since prime Scottie Pippen. Last season’s Raptors were a superficially good defensive team that fell apart against top offenses. This looks, and feels, different. It feels real.

We haven’t even talked about the bench. The Raptors are not going to become the Warriors. We may never see another team that good. But unless Boston gets its offense together — and it has, like, six months — Toronto will emerge as Golden State’s greatest threat.

2. NIkola Jokic’s long-distance post-ups

Through five games, Jokic has been one of the league’s three or four best offensive players: 23 points and six dimes per game on elite shooting from everywhere. He came within one missed throw of a Laettner in an 35-11-11 devouring of Deandre Ayton and the Suns last week. If Jokic sustains 40 percent 3-point shooting on a high volume, he has a chance to redefine the entire concept of a stretch center. A man this large has never assumed this degree of efficient pass-dribble-shoot control of an offense from 30 feet and in.

Jokic is comfortable doing anything from that distance, including dribbling into post-ups against smaller guys:

Most behemoths don’t have tight enough handles to dribble naked that far from the rim; little guys poke the ball away. Jokic’s girth helps him keep gnats at bay. (He still needs to get in better shape.)

Jokic has ranked as one of the league’s dozen most effective post-up players in each of the past two seasons — even as he shot 44 percent out of post-ups last season, down from a preposterous 58 percent in 2016-17, per NBA.com. His passing from the block is that precise and inventive. He doesn’t even need to draw help to unlock open cutters. Hell, those cutters don’t even have to be open. If a defender has his back turned at the wrong moment, Jokic will slip a pass under the poor guy’s armpit.

These dribble-drive post-ups are a handy tool. Teams switch in a pinch on Jokic pick-and-pops — especially with the shot clock in single digits. Jokic’s comfort exploiting those switches will keep a lot of Denver possessions profitable.

3. Big men passing out of layups

I’m pro-analytics, or at least analytics-adjacent. We all get how much greater three is than two — 50 percent greater! Those who don’t are goink extinct.

There is clear utility in so-so finishers bailing midair on high-wire layups, and kicking to open corner shooters. Some guys overdo it, but the math works.

I draw the line at big guys’ forfeiting close-range shots. Like, Jarrett Allen, what are you doing?

You’re 6-foot-10! That guy at waist level is Trey Burke! You shot 77 percent from the line last season. Your team is up by three with 35 seconds left; take the sure points!

It worked here for Alex Len, but this is still an act of surrender. It is offensive.

Seven-footers are put on earth to cram on smaller humans. Rise up, shoulder-block interlopers out of bounds, and dunk. Dare defenders to clothesline you. Be Goliath.

4. Zach LaVine, coming at you

It’s easy to poke fun at LaVine. Chicago’s defense is as clueless as anticipated, and LaVine is part of that. He’ll take three or four nutty shots every game. He loves a contested long 2-pointer. He has no interest in Fred Hoiberg’s proposed rule that every player gets half a second to decide whether to shoot, drive, or pass.

But he’s averaging 32 points per game (!) on 57 percent shooting (!!), and he’s attacking the rim with a new ferocity — a fantastic sign in Year 2 after an ACL tear. When big men drop back against LaVine in the pick-and-roll, he is using the extra space as a runway to zip around them:

Wait at the rim, and he’ll rev up, hit you in midair, and finish through you — with either hand.

LaVine is shooting a LeBronian 77 percent in the restricted area. He has hit 67 percent of his attempts out of drives — one of the best marks in the league. He is getting to the line nine times per game — triple his career average.

LaVine isn’t a good enough playmaker to work as the true alpha dog for a top-level offense. But if he attacks like this and hits 40 percent of his 3s, LaVine can be a monster plus on that end.

5. Anthony Davis, fully operational

Uh-oh.

UH-OH.

Four years ago, New Orleans’ coaches told me about the challenge of teaching Davis two- and three-dribble moves. He was only comfortable bouncing it once, and then stretching himself toward the rim for an awkward fling shot.

Now he’s toasting fools with hesitation moves and in-and-out dribbles in the open court. God help us. He’s using those moves to draw more contact; Davis is averaging a ridiculous 11 foul shots per game.

On defense, Davis has carried over the heightened awareness and calm that marked his play late last season. He has reached that rare state of consciousness at which an elite defender manipulates offenses instead of reacting to them. As pick-and-roll ball handlers creep into his territory, Davis slides along with them, arms spread wide to threaten any pass to his guy. He doesn’t jump, or flinch at fakes. He reveals nothing. Opposing guards finally face a decision — pass or shoot? — and only then does Davis pounce.

He leads the league in blocks, again. Opponents are shooting just 45 percent at the rim when he’s nearby — an elite figure in any season, per NBA.com. The Pelicans have allowed 100.9 points per 100 possessions with Davis on the floor — and 122 when he rests. Opponents have scored only about 0.8 points per possession on any trip featuring a pick-and-roll targeting Davis — a figure that would have been the stingiest among all big men last season, per Second Spectrum. (The numbers are just as impressive if you isolate shots taken directly out of those pick-and-rolls, or by players one pass away.)

Davis is becoming everything even the most hopeful among us thought he could be. He is coming for it all — MVP, Defensive Player of the Year, your team’s soul.

6. Nerlens Noel, chasing laser pointers

When people wonder why Noel doesn’t play more despite hoarding steals and blocks — why no coach has ever trusted him — show them clips like this:

Noel is perhaps the league’s most egregious block chaser. Even Hassan Whiteside might suggest that Noel chill.

Noel has almost zero chance of accomplishing anything by lunging at Justin Jackson‘s baseline hope shot. That is a low points-per-play shot, anyway — well-covered, off-balance, from a weird angle. Both of Noel’s feet are on the floor when the ball leaves Jackson’s fingertips.

Basic numbers say Noel is a decent defensive rebounder; he has grabbed about 22 percent of opponent misses during his career — average-ish for a big guy. Those numbers mislead. Noel’s teams have fared a hair worse on the defensive glass with him on the floor over five seasons, per NBA.com. (Most were bad regardless.)

Tracking data paints him as a below-average defensive rebounder when accounting for his location at the moment a shot goes up, per Second Spectrum. He is a not a box-out fiend in the vein of the Lopez twins — a grunt who sacrifices his own rebounding to plow away multiple enemies.

There is an argument that coaches are oversensitive to mistakes like this. Fundamental errors incense them on such a visceral level as to obscure the good stuff players like Noel bring — including things, like steals and blocks, that are products of an overcaffeinated style.

But that reasoning has never swayed me with Noel. He is out of scheme all the time. He’s not a good enough offensive player — like, say, Karl-Anthony Towns — to live with him undoing your defense.

There is a good player in here, somewhere. Noel is super-talented. He’s a good passer. He needs to realize his influence on the game will grow if he plays under control.

7. Jeremy Lamb, stepping in

The Hornets under James Borrego are going positively wild. They are heaving 3s and testing the limits of small ball by slotting Marvin Williams and Michael Kidd-Gilchrist at center. Sliding Lamb into Kidd-Gilchrist’s starting spot was step one of that makeover.

But Lamb is leaving fly-by triples on the table:

He does not have the sidestep that is all the rage even among average shooters. The sidestep is harder than it looks; Lamb is working on it, Charlotte’s coaches say. Atlanta’s old coaching staff would tell you it took Taurean Prince many months of repetition in private before he felt comfortable busting the sidestep out in games. Now he does it all the time.

Here’s hoping Lamb masters this. He’s not a good enough midrange shooter or drive-and-kick guy to give up open triples.

8. TJ Warren, man-watching

We hear all the time about ball-watching as a sin. It’s easy to spot. It leads to backdoor cuts. It smacks (sometimes falsely) of greed: an obsession with possessing the ball so that one might then shoot it.

We hear less about the inverse: when a defender on the weak side fixates on his man, oblivious to the ball and any help responsibilities. You might call it man-watching. Coaches call it “hugging,” and it can be just as damaging as ball-watching.

Warren is a serial hugger. That may not seem important: Warren isn’t particularly big, stout, or long; is he really going to scare people by darting into the paint?

He might. Bodies flashing into the paint at the right moment make even the most powerful ball handlers pause. You can’t just mow over people who get there first.

Warren is a gifted scorer. If his early-season 3-point bonanza proves real, he becomes a very dangerous offensive player — even when he doesn’t have the ball. But until he internalizes some basic principles of team defense, a lot of his game will be empty calories.

9. The state of Jeremy Lin

Jeremy Lin cannot be 100 percent recovered from the knee injury that cost him last season. He moves with a leaden creakiness — unable to gain separation, unsteady in traffic, glued to the ground. He does not look like an NBA player right now.

Opponents have stifled the Hawks when Lin runs the show solo. Atlanta has even scrapped some of Lin’s second-half stints in favor of lineups featuring no point guard.

Neither the Hawks nor the Nets expected Lin to open the season at full strength. But Lin’s early struggles reinforce confusion over why Atlanta bothered absorbing him into its cap space as part of what was effectively a three-team trade with Brooklyn and Denver. Brooklyn dumped Lin to free room for Denver’s unwanted contracts — and a top-12-protected first-round pick that came with them. The Hawks acted as middleman when they could have done the Denver deal themselves.

The Hawks’ defense: They knew they were going to trade Dennis Schroder, and wanted a veteran point guard to ease Young in. The Schroder deal with Oklahoma City netted them a lottery-protected first-round pick in the 2022 draft, which could feature both one-and-done players and 2022 high school graduates.

But they could have gotten an equivalent first-rounder from the Nuggets, and signed any number of cheapo minimum-salaried point guards — Shabazz Napier and Seth Curry come to mind — in Lin’s place. It’s not as if they are easing Young in, anyway.

(I’m more bullish on Young after his first week-plus in the NBA, by the way. He’s a train wreck on defense, but he’s as advertised on the other end. Defenders press Young 30-plus feet from the hoop, and he’s already good at leveraging that to slip by them, keep them on his hip, and do damage.)

10. C Us Rise

This is the 2018-19 version of Uknickcorn — the Knicks’ jumbled attempt last season to pile a new nickname atop Kristaps Porzingis‘ existing one.

Even if my conscious mind understands the intent, the visual presentation scrambles the brain circuitry responsible for reading and language comprehension. My brain downloads “Cuss Rise.” I see “Cuss Crise.” I wonder for a second if it is a reference to Syracuse — the “Cuse” — for some reason. The giant capital “C” enveloping “us” and “rise” is not helping.

Please, scrap this immediately. You are the freaking Boston Celtics. Keep it simple.

Source:ESPN