A version of this story appears in ESPN The Magazine’s Sept. 10 NFL Preview issue. Subscribe today!

Nelson Stewart didn’t ask why Odell Beckham Jr. needed film. He knew. Stewart, Odell’s former coach at Isidore Newman School in New Orleans, was in his office this summer watching old plays. He’s a former teammate of Peyton Manning’s and a close friend of Eli’s, both Newman alums as well, and he keeps a grass-stained Beckham No. 3 Newman jersey in his office drawer as a reminder of his fortune to witness so much transcendent talent at such a small school. On this day, he filmed a few touchdowns off his computer screen and texted them to Odell, who replied: “lol coach i really need my high school highlights.”

It has been a difficult and uncertain offseason for Beckham, years in the making. Ever since The Catch — the twisting, levitating, horizontal, three-fingertipped, pass-interfered-with, impossible touchdown against the Cowboys in 2014 — and the celebrity and scrutiny that attended it, he has lost some of his old joy. And along with it, maybe his edge. After the fights and meltdowns, the boat trip, the dog pee celebration and the sparring match with a kicking cage, not to mention an uptick in dropped passes, he broke his ankle in October and missed most of last season. Then in March, he was sued by a man who claims he was beaten up at Beckham’s LA residence in January-in a countersuit, Beckham would deny involvement. That same man later claimed he had evidence that Beckham tried to illegally pay a woman $1,000 for sex, which Beckham denied as well. Also in March, a video of Beckham in bed in Paris with an aspiring model and what appeared to be illegal drugs went viral. Later in the month, the Giants, wary of meeting his desire to be the NFL’s highest-paid player, listened to trade offers, and owner John Mara publicly implied that it was time for the 25-year-old wideout to grow up.

Coach Stewart has known Odell since he was 9, and like most in Beckham’s inner circle, he knows The Catch spawned a mania that neither the receiver nor his crew nor the Giants knew how to handle. To him, Odell is not OBJ but “3.” Where others see the most viral player of the viral era, Stewart sees “an old soul” who at heart is “pretty nostalgic.” So he knew what Odell needed when he asked to see old plays, and he delivered the clips: a fade for a touchdown against De La Salle; a stop-and-go for six in a scrimmage against East Jefferson; a screen that Odell took the distance against Bogalusa; and finally, a leaping one-handed snare against East Feliciana, his genius in its infancy.

“Thank u,” Beckham texted after looking back through 25 minutes of his old self — a reminder of what beauty looked like before it was broken.

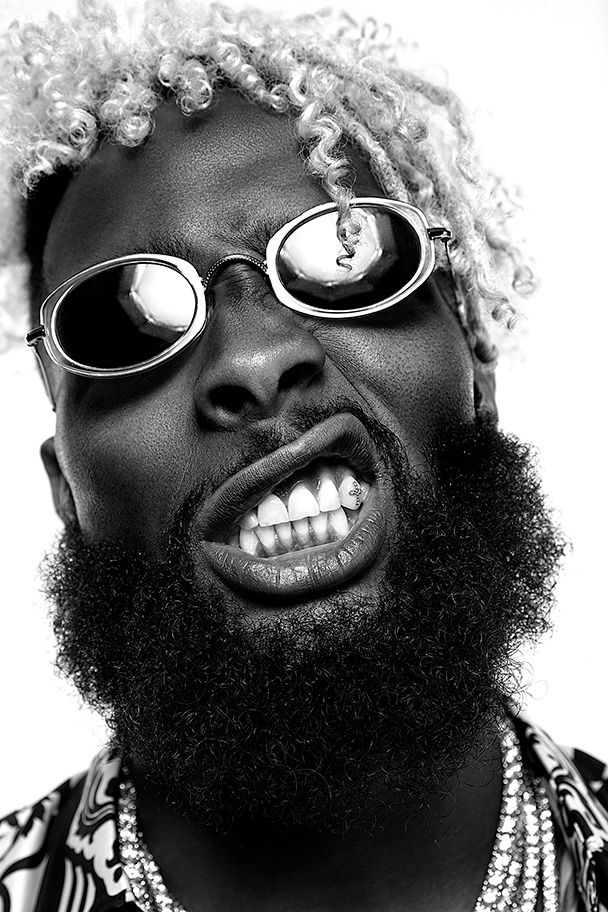

Odell is dragging. He rolls out of a golf cart on a June day, the last to take the field at his own youth football camp on a high school field in New Jersey. Word is he was out late last night, but who knows. He yawns and removes the white hoodie surrounding his head — his standard TMZ disguise — and rubs his hair, curls spilling over, the hair of many kids at his camp, a factory line of OBJs. The kids are vibrating, and the camp’s emcee is screaming into a microphone, but Odell, usually bouncing as if set to his own soundtrack, isn’t quite ready for his own arrival.

“I don’t have as much energy as him,” Odell says, alluding to the host. “Let’s just have fun.”

“Everybody on your feet!” the host says. “Coach Beckham likes straight lines!”

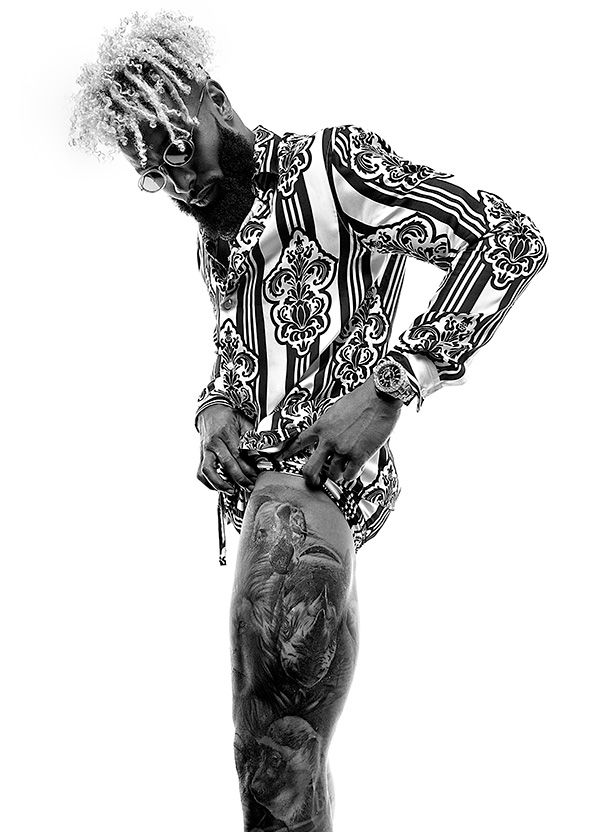

At the moment, Coach Beckham might like more sleep. He leads everyone in jumping jacks, barely lifting his arms above his shoulders, and then slowly changes shirts, revealing a body with every muscle curved and pronounced, blanketed in tattoos to the jaw, an extravagant expression of self, not just the body of an athlete but the body of a star, designed to be unveiled and studied and celebrated. For the past year, NFL executives have privately admired the way the NBA promotes its players. If football wants a face to rally around, it could be Beckham — with his singular aerial artistry, historic productivity and signature dance moves. But there’s a gulf between his potential and the reality of his career, and even after the Giants signed him to a five-year, $95 million deal — a record for wide receivers — trust will remain an issue. Nobody knows whether he will become an immortal player or merely one remembered for an immortal moment in 2014.

The stakes are high. In the spring, when the Giants were listening to trade inquiries — the Rams and 49ers were the two teams reported to be interested, but there were others — one curious club hired a private investigator to track Beckham. The Paris video had introduced drug-use rumors that teams wanted to run down, even if recreational drug use falls below his surgically repaired ankle on most teams’ list of concerns. The PI’s report set off no alarms, but despite the Giants being “50-50” on their willingness to trade him, according to a league source with knowledge of the situation, no team would meet their asking price, which was believed to be a pair of first-rounders.

So here’s Odell at his camp, learning that holding on to his trademark joy can be a grind. He was supposed to meet with reporters today, but he canceled. He limited most of his public comments this offseason to benign Instagram posts. He declined a formal interview for this story but didn’t mind my observing him up close for hours on both coasts. He’s said in the past that his words don’t mean much. Still, his mother, Heather Van Norman, is with him at his camp — she’s rarely far away from her son — and she’s chatting up reporters, even those who have been critical. A few reporters sense a warm front, an attempted reset.

Beckham signs a stack of photos and jerseys and helmets, his hands — so long and soft that his catches sound gentler than those of other receivers — dwarfing a Sharpie. A little later he stands alone and jogs out to make the rounds of the campers, pushing off his left ankle, which has a red scar running so high it looks like another tattoo.

The Catch spawned a mania that neither the receiver nor his crew nor the Giants knew how to handle. Randall Slavin for ESPN

“Do one-handed!” a kid says.

“I can’t catch one-handed,” Odell jokes.

The kids are running routes and dropping passes. Odell is throwing. He played some quarterback at Newman, the Tebow jump throw his signature move. They’re dropping passes because they’re trying to catch them like Odell. He wants to teach them how to properly catch a football, with two hands forming a diamond. They want him to teach them how to OBJ it. He can’t; his gifts and drive are not transferable. But the kids are having fun as the ball bounces off their single outstretched hand, and he isn’t going to ruin it. Finally, a kid snares the ball with his right palm. Odell wags his finger, timed to the beat of the music blasting, and curls his face, at once handsome and vulnerable and volatile, into an approving grin.

Beckham’s catch — The Catch — was a long four years ago, and it marked both the beginning and the end of something. He told his mother at age 4 that he would become a professional athlete. And although he was blessed to be both born with and surrounded by elite athleticism — she was a six-time All-American in track; his father, Odell Sr., was a running back at LSU; his stepfather, Derek Mills, was an Olympic gold medalist in the 4×400 relay — he authored his dreams the old-fashioned way: by practicing. In high school, he used rubber bands to build finger strength, training a lone hand to be the only one necessary. He broke the rules for catching a football by catching it like a baseball, his palm up when it was supposed to be down and down when it was supposed to be up. He raised the ante on himself, both revolutionizing and evolving his craft, first at Newman, then at LSU and then in the NFL, catching one-handed while he did handstands, competing against conventionalism as much as any defense. He imagined his own brand of immortality, and in the split seconds in which he was the only person in the world reacting the way he reacted to an arriving spiral, he could feel it. Odell Sr. had told his son, “You gotta do something strange for a piece of change.” Coming up, Odell wanted to be exotic. He wanted the extraordinary to seem routine. And on Nov. 23, 2014, when Eli Manning threw deep down the right sideline and Dallas defensive tackle Henry Melton turned to Giants offensive tackle Geoff Schwartz and said, “Oh s—,” that’s what it was: an impossible moment willed inevitable.

The Catch catapulted Odell into fast friendships with LeBron and Jordan and Drake. It also changed football, injecting an original beauty into a familiar violence, drawing in millennials to an aging fan base, showcasing a non-quarterback who could produce the spectacular. People started showing up to watch Beckham in warm-ups, as if he were Mark McGwire taking batting practice in ’98. Crowds waited for him outside of the team bus and chased him across hotel lobbies. He had just turned 22 and found himself both on the sports page and the gossip page, and the intensity with which people followed him, the extent to which they craved some next bit of magic from him, was often overwhelming. It quickly became uncontrollable. He’d sometimes escape on off-days to LA, where he could be one celebrity among hundreds. The Giants worried that he might be susceptible to peer pressure and that he wasn’t taking care of his body, and he later confessed that he didn’t always do that, even as he led the league in receiving yards per game and scored 12 touchdowns and was named Offensive Rookie of the Year. “Odell became a one-name celebrity,” Schwartz says. “That’s the leap he made overnight.”

In that 2015 offseason, Odell became the Madden cover boy and posed nude for the Body Issue of ESPN The Magazine. But he wasn’t quite right. One March evening, he vented cryptically for three hours on Twitter: “At the end of the day I will never let another human being steal my joy in life” … “Finding me, until then the rest is almost irrelevant.” He looked exhausted and detached and disinterested at an autograph signing event that summer on Long Island, never removing his backpack. And by the time he arrived at training camp for his second season, he told the New York Post that the football field had become an “escape,” a “getaway.”

Even that feeling didn’t last long. Ben McAdoo, the Giants’ offensive coordinator at the time and later the team’s head coach, told others in the organization, “The Catch was the worst thing that happened to him.”

Beckham told his mother at age 4 that he would become a professional athlete. Randall Slavin for ESPN

Beckham didn’t slack off, despite his comfort in celebrity circles. He pushed so hard in practice during the 2015 season that coaches described him as a team leader. He gave teammates blue Beats headphones for Christmas and often held the phone himself to ensure that fans’ selfies came out just right. Coaches sometimes caught him twirling his hair and staring off in the distance during meetings, but he recalled the material perfectly when quizzed and did killer impressions of members of the staff, particularly offensive assistant coach Ryan Roeder’s blitz speeches.

He worked hard to prove that being Odell — being OBJ — came easily, but something was off. That much people around him knew. He committed the cardinal sin of modern fame — he replied to tweets — and tried not to take personal insults, about his style and play, personally. But there’s a huge difference between the joy of being respected for your craft and being pawed at for it, and Beckham struggled to live in the space between. During downtime at the Giants’ facility, he’d brood just enough to let on that something was bothering him, but he also seemed tired of being asked how he was doing. He groused in 2015 about the constant media attention but would sometimes FaceTime reporters just to talk. Anyone with a phone could observe his life, but nobody knew what it was like to live it. “I’m the only one who goes through what I go through,” he later said.

Beckham’s talent and temperament had made him seem vulnerable, and in the NFL, vulnerability always catches up to talent. Going back to high school, he’s had a ritual of transforming himself before games. “When he’d put on his helmet,” Stewart says, “he was a completely different kid.” The routine starts slow, with his headphones on, and as Giants receiver Sterling Shepard says, “He amps his way up.” He bobs his head and wags his finger and by the time he takes the field for warm-ups, sometimes pretending to be the Joker, he’s preening as much as he’s dancing, psyching himself into a state of grace when most players psych themselves into a state of rage. It made him ripe for blowback in 2015, aimed at the heart of what he believed in and how he saw himself. Defensive coordinators and players had spent the previous offseason considering ways to defend him, and a clue arrived late in his rookie year, when the Rams hit him hard and out of bounds, igniting an all-out brawl. It was an answer as old as football.

Get inside his head.

And beat the living hell out of him.

Source:ESPN